Demystifying Deep Learning: Part 7

Debugging the Learning Curve

September 02, 2018

5 min read

Introduction

We’ve talked a lot about training our model, and improving our optimisation algorithms to really get the best out of it, but we’re missing one piece of the puzzle here - what even is the best? How do we know our model will actually perform better?

You may have noticed that our neural network had a much lower training set error than test set error both when we trained it on the housing price dataset, and when we trained it on the breast cancer dataset.

This post is dedicated to looking at debugging your model’s performance - for the first time since Part 1 of the series, we’ll be revisiting the idea of training, validation and test sets.

Learning Curves

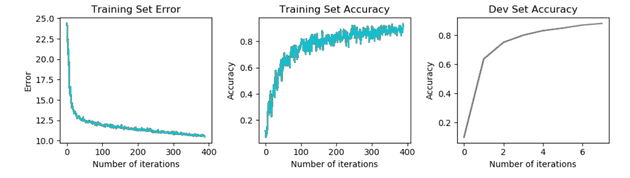

The best way to gain insight into the performance of a model is through plotting learning curves. Learning curves plot a key evaluation metric against the iteration number, to see how it changes as the model is training. The metric is typically either cost or accuracy - although the metrics may differ based on your problem - for example a skewed dataset may use the F1 score instead.

Regardless of the task, plotting the cost on the training set is a must, since it provides a clear indication of whether the model is learning or not - if it is not decreasing, or worse, increasing, this clearly highlights there is something wrong with the underlying model.

Looking at the cost on the training set to see whether the model is learning or not is just the tip of the iceberg though.

Bias vs Variance

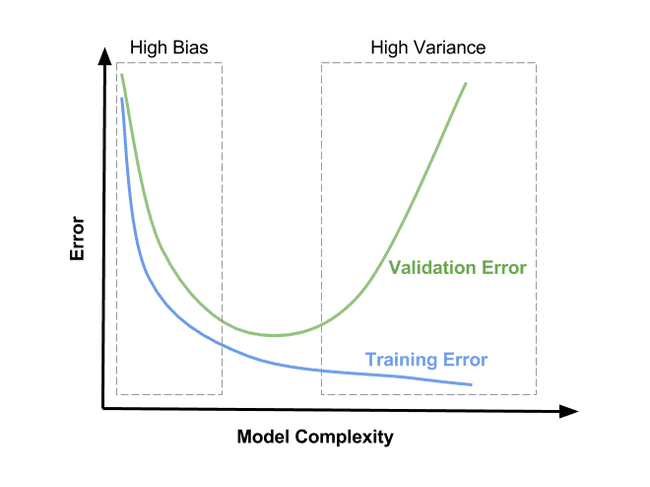

Two properties of a machine learning model we are interested in when debugging learning are bias and variance - these quantify two sources of error in a machine learning model. Together they form the bias-variance tradeoff inherent in most machine learning models.

Bias:

- this quantifies how far the expected value predicted by the model is from the true value .

If a model has high bias, it is said to underfit the data. This is when the model doesn’t have the capacity to learn a complex enough representation of the data - so has a high error in the prediction (high bias). An example of this is in simple models like linear and logistic regression that try to fit a straight line relationship, when the line of best fit is a more complex curve.

A model with high bias will have high training and validation set error - if the learning curve plateaus early with a high error, use a more complex model. Typically neural networks don’t suffer from this issue, although if this is the case it is worth increasing the number of hidden layers, or number of hidden units in each layer.

Variance:

- this quantifies how much the prediction of the model varies as a function of the input data.

If the model has high variance, we say that it is overfitting the data, since a small change in the input results in a different prediction - so the model has learnt the nuances of the training data too well, even fitting to any underlying noise in the training data.

High variance hampers the model’s ability to generalise since rather than learning a more general, robust representation, it has instead learnt a representation very specific to that particular set of input data.

A model with high variance typically has a low training set error but a high validation error when the learning curves are plotted.

A slightly less common form of overfitting is if the validation set has a higher error than the test set - this suggests we’ve tuned our hyperparameters too well and again learnt a representation that is specific to the validation set. A typical fix is to ensure our validation is not too small, and to ensure it comes from the same distribution as the test set - this ensures it has the variety and size and also reflects the actual problem’s data we are trying to fit.

Regularisation:

Neural networks tend to suffer from high variance, especially as they get deeper and more complicated - to combat this we use a set of regularisation techniques that ensure the model still generalises well.

Early stopping

One simple technique is stopping the training process early when the validation error plateaus or starts to decrease. This is a good regularisation technique since it stops the training before the model starts to memorise the nuances of the training set, so it is still able to generalise.

L1/L2 Regularisation:

L1 and L2 regularisation both involve adding an additional term to the cost function penalising the size of the weights. For L1 it is :

Whereas for L2 regularisation the additional term is:

Having large weights means that a small change in the input causes a large change in output when multiplied by the weights. By adding a penalty term, we ensure the weights are small, so the model’s output is not as sensitive to a small change in the input.

In the equations above, is a hyperparameter, used to control to rate of regularisation and thus the tradeoff between bias and variance. If it is too large, then regularisation is too strong and the model will underfit. If it is too small, then the model will continue to overfit.

Data augmentation

Often a model is able to learn the nuances of a relatively small training set, so by increasing the size of the training set the model cannot “memorise” patterns specific to the examples seen. The augmented dataset should also hopefully have more variation in the input, so the model will generalise to a wider range of input.

Adding noise to training

Another way of ensuring the data isn’t susceptible to overfitting is to add noise to the data. One way of noise is distortion of images, or adding noise by randomly sampling from a Gaussian distribution and adding that to random input values.

Noise isn’t just limited to the inputs - they can also be added to the weights or even the gradients when learning.

Dropout

This is a technique where, on each forward pass through the network in training, we disable the activations of neurons in that layer at random. The idea behind this is that the neurons then do not rely heavily on another particular neuron’s activations,since there is a chance that the neuron may be disabled the next pass. This in turn leads to more robust representations learnt by the neurons.

Another way of looking at Dropout is through ensemble learning, is that if there are neurons in a given layer, and each can be turned on/off, then there are possible network configurations, and in essence we are taking the ensemble prediction over all these models.

By obtaining our prediction from these models in an ensemble setup, our prediction is more likely to generalise rather than if we were to only use one model’s prediction.

Code:

#determine which neurons are on/off based on dropout probabilitycache["dropout"+ str(l)] = np.random.rand(*cache['A' + str(l)].shape) <= keep_probcache['A' + str(l)] = np.multiply(cache['A' + str(l)], cache["dropout"+ str(l)])cache['A' + str(l)]/= keep_prob

To see an example of Dropout in a neural network, you can see this notebook.

Summary:

A quick learning curve case-by-case wrap up:

Training, validation and test set error all low and roughly same - Model is learning and generalising well - no concerns.

Training error high - suffering from high bias - use a more complex model.

Training error low, validation set error high - model is overfitting - use larger dataset or increase regularisation

Training and validation set error low, test set error high - model has overfit to validation set - use a larger validation set / ensure same validation/test distribution

These are general techniques useful not just for neural networks, but for debugging machine learning models in general. We’ve also looked at specific techniques to prevent neural networks from overfitting.

So far in the series we have covered the foundations of standard feedforward neural networksand how we can get the best out of them, both in terms of optimising learning and ensuring generalisation.

Now that we have a strong base, we will shift our attention to more specialised neural network architectures in the next blog post.